Do You Know These Strangers In Your Brain?

Quick article navigation

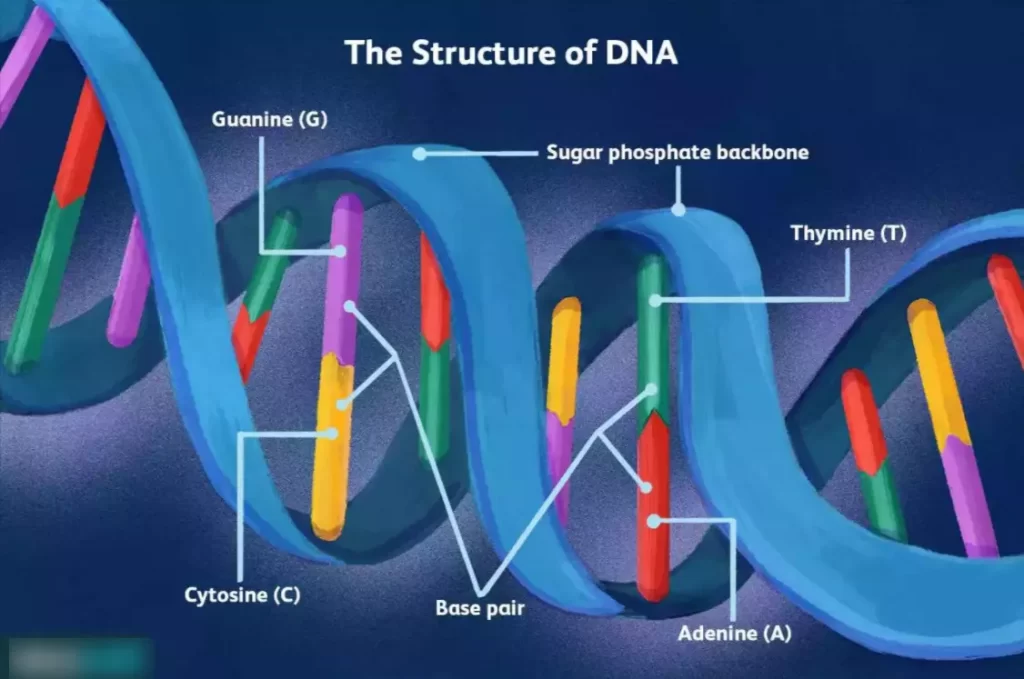

Do You Know These Strangers In Your Brain? Do you know what’s the most dangerous thing for a living organism like humans? It’s cell division – a complex process that involves replication, the unspooling of DNA, the assembling of genomes from two halves and various other complex processes.

What is the brain? The brain is a complex organ that controls thought, memory, emotion, touch, motor skills, vision, breathing, temperature, hunger and every process that regulates our body. Together, the brain and spinal cord that extends from it make up the central nervous system, or CNS.

At some stage, DNA polymerase tries to copy the exact DNA sequence, but the chances are that cells may make a mistake at any of these steps during the process, which can cost the organisms their life. However, this is also essential for their evolution.

Without them, the search algorithm of life will stop. There are wandering snippets of DNA (called transposon), often hidden in human genomes, that keep copying and pasting themselves randomly. Though they don’t carry important information, they constitute approximately 50 per cent of the entire genetic material in our body.

These are not harmful as they are often neutralized by other ‘retrotransposons’. So in many ways, it’s like a Mafioso—where ‘transposons’ and ‘retrotransposons’ are fighting for supremacy. So, in a sense, our body is a genetic battlefield for these warriors.

We are the result of trillions and trillions of successful cell divisions and genetic mutations, and so the friendly retrotransposons effectively dominate the body. And this is where the story ends.

Somewhere around 2000, Rusty Gage, the neurobiologist at the Salk Institute, found something strange happening when he was studying the development of adult brain cells. What he saw – it shocked him. He just could not believe it.

‘Transposons-the destroyers’ were not only present, but they were ‘dancing’ and ‘singing’.It evidently disturbed the mind of the Gaze. He kept thinking about it the whole day. It deprived him of the night sleep.

Whether transposons keep tampering with the DNA of every future neuron—such questions keep flooding his mind. So in that way, each neuron was not giving birth to a similar neuron, it was producing a neuron with a different genome. After several years of study and diligent research, it was found that – the cells in the same brain may indeed genetically different from one another.

But this does not happen in the other part of the body. The cilia tissues, that protects our lungs, is genetically similar to the blood cells circulating in arteries, though they look very different from each other.

So according to Gage’s theory: Transposons makes this transformation possible, which is quite complex. Our genes are not alone capable of doing this. So every brain is born through a different evolution system. A son’s cerebral ecosystem may be quite distinct from his mother’s.

Thus, there is not a standard genome in the brain. That’s probably the reason the genetic predisposition of every brain, despite being born from the same parent brain, is different. To explain it Gaze explained a hypothetical experiment:

Gage described a hypothetical experiment involving the animals: “Take ten mice from the same mother. All of them are of the same gender, age and put them in a similar controlled environment – such as keep all of them in an open field. But, their behaviour will be different. Some of them will freeze from fear while others will start circling in frenzy.

In fact, a number of brain disorders may be due to this transposon, but it’s not clear whether there is any causal connection.

Gage quickly recognized that this strange revelation might help answer a longstanding question in neuroscience: how does nature wire up a system as complex as the human brain?

The strange thing about transposons, is they bely the traditional evolution theory, they copy and splice rapidly. They can add more DNA to a population, without adding new genes.

In a short time—corresponding to fewer than a dozen or so generations – they can add more DNA to a population, inflating the total volume of DNA without adding new genes.

Some species appear to have large volumes of DNA that were assembled this way. About 44 per cent of human DNA consists of repetitive elements, much of which came from transposons. On the contrary, the evolution process is gradual.

However, perhaps this strange genetic hitchhiking on our DNA have shaped the process of human evolution. It has helped us become who we are.